Online activists are facing abuse from misogynists and paid troll armies, but asking for laws to protect us from online abuse may come back to haunt us.

The great freedoms offered for new voices, innovative media and human rights activism, goes hand-in-hand with real dangers on the online networking space, that was the subject of feisty discussion at the IAWRT biennial in New Delhi, India and is under scrutiny around the globe. The growth of online networking and media has complicated our understanding of media ethics, and of how to guarantee freedom of speech. It also muddies the issue of censorship and how it operates in many countries.

By Nonee Walsh

It was the subject of feisty discussion at the IAWRT biennial in New Delhi, India, and is under scrutiny around the globe. Ilang Ilang Quijano, the editor of online Pinoy Weekly in the Philippines, was sued for libel early in her career for printing a well-documented story about the environmental and health impacts of aerial spraying on a banana plantation. Despite being dismissed by a lower court, she says an antiquated law was used to intimidate, harass and financially penalise her publication for many years. A new cyber-crime prevention act which was aimed at criminal activity continues to threaten free media as it still includes libel and online journalists can be jailed for 6-12 years.

Censorship

However in one of the world’s most dangerous countries for journalists, she says “media killings are highest form of censorship.” Ms Quijano says of 174 journalist killings over recent  decades there have only been 11 convictions and that is “only killers not the masterminds.” She believes the government wants to ensure no avenue for expression exists that is free from control by a rich and powerful elite.

decades there have only been 11 convictions and that is “only killers not the masterminds.” She believes the government wants to ensure no avenue for expression exists that is free from control by a rich and powerful elite.

In a very different country, Sri Lanka, Kishali Pinto-Jayawardena, a human rights lawyer and columnist with the Sunday Times, says there was a similar story, where mass killings had journalists living with a chilling fear which lead almost to the complete annihilation of free media, making censorship redundant.

While she was among the women who were brave enough, as the Sri Lankan joke went, “had the balls,” to keep speaking out, Pinto-Jayawardena says tthe shutdown of the free voices in traditional media meant that the online space became the arena where momentum was gained to vote out the Rajapaksa government and replace it with a government promising more freedom.

However, six months after his election, President Maithripala Sirisena’s government has revived the Press Council – a body that can sanction media and imprison journalists. The move has been condemned by Reporters without Borders, amongst others.

Pictured left to right: Dr Anja Kovacsthe Director of the Internet Democracy Project in Delhi, Ilang Ilang Quijano and Kishali Pinto-Jayawardena.

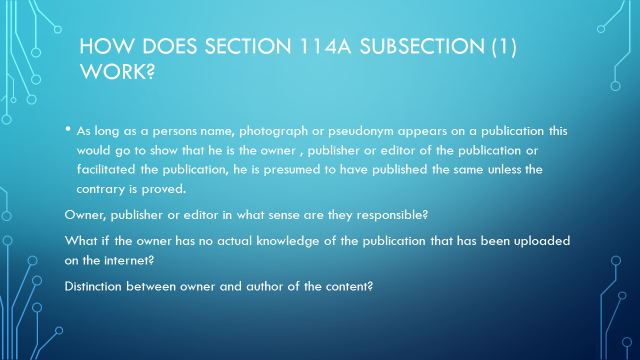

In Malaysia, too, new cyber-offences were created in 2012, under reforms responding to some demands of media freedom campaigners. However, the controversial section 114A of the Evidence act. was also enacted, the government said, to protect against anonymous cyber-crime, such as threats and harassment. It makes the subscriber of an Internet Service Provider (ISP) prove that a certain statement was not published by him or her, and third parties such as search engines, discussion hosts and computer or mobile phone owners, are deemed to be publishers. Cirami Mastura Drahaman from Sunway University in Malaysia says the reversal of the burden of proof has “a chilling effect,” as they have to prove they were not publishers to avoid liability for defamation. She told a communications law conference at Melbourne University that it “bodes ill for netizens” as not knowing about publications (such as comments) is not a defence, and site operators are not given reasonable time to remove content.

In Malaysia, too, new cyber-offences were created in 2012, under reforms responding to some demands of media freedom campaigners. However, the controversial section 114A of the Evidence act. was also enacted, the government said, to protect against anonymous cyber-crime, such as threats and harassment. It makes the subscriber of an Internet Service Provider (ISP) prove that a certain statement was not published by him or her, and third parties such as search engines, discussion hosts and computer or mobile phone owners, are deemed to be publishers. Cirami Mastura Drahaman from Sunway University in Malaysia says the reversal of the burden of proof has “a chilling effect,” as they have to prove they were not publishers to avoid liability for defamation. She told a communications law conference at Melbourne University that it “bodes ill for netizens” as not knowing about publications (such as comments) is not a defence, and site operators are not given reasonable time to remove content.

The ‘Stop 114A campaign’ included an Internet Blackout Day coordinated by the Centre for Independent Journalism but the government was unmoved, and it is now law with numerus cases over social media posts coming to court.

Online campaigns do have some power, a massive social media campaign on behalf of MaryJane Veloso, a trafficked Philippines woman on death row in Indonesia for alleged drug importing, is a good news story about online opportunities for human rights campaigns. One petition to have her released on Change.org gained over 250,000 signatures. However that is a salutatory lesson in both the successes and the dangers of the online space. Mary Jane Veloso was given a last minute reprieve in April this year, five years after her arrest, saved finally by a last minute appeal by the Philippines President Benigno Aquino.

Hatespeech and violence

However Ilang Ilang Quijano says after Mary Jane Veloso’s mother criticised the Philippine government’s tardy response to her daughter’s plight, and did not thank it as a saviour, a large amount of online abuse ensued under the hashtag – firing squad for Celia Veloso. Ms Quano’s assessment was that the campaign was instigated by government trolls (schills) she calls them “paid troll armies.”

It would appear that the decision by the Philippine Daily Inquirer, to publicise the Veloso abuse campaign, like similar decisions to publicise fatwahs, for example, in Pakistan, cannot meet the test of ethical journalism, which is proposed by the Ethical Journalism Network. Director Aiden White asks: “Who draws the red line – the frontiers of tolerance – between hate speech and free expression? “We argue that it should be drawn by journalists, motivated by humanity.” The network has devised a five point test which journalists could apply to judge whether reporting commentray is propogating hate speech:

It would appear that the decision by the Philippine Daily Inquirer, to publicise the Veloso abuse campaign, like similar decisions to publicise fatwahs, for example, in Pakistan, cannot meet the test of ethical journalism, which is proposed by the Ethical Journalism Network. Director Aiden White asks: “Who draws the red line – the frontiers of tolerance – between hate speech and free expression? “We argue that it should be drawn by journalists, motivated by humanity.” The network has devised a five point test which journalists could apply to judge whether reporting commentray is propogating hate speech:

*Positional Status of the speaker

*Reach and impact of the speech

*Real intention of the speech

*The content and form of the speech

*Economic and social and political context of the speech

“Online abuse or misogyny is the single most serious threat to journalism, and there is a need to return to the basic strengths of journalism, which is not free expression” Aiden White says.“It is constrained expression, we operate in a framework of ethical values, we have public purpose and our form of expression is ‘other regarding’… We take into account, we consider the impact of what we do, what we say, what we broadcast and its impact on others. Social networking is self-regarding.”

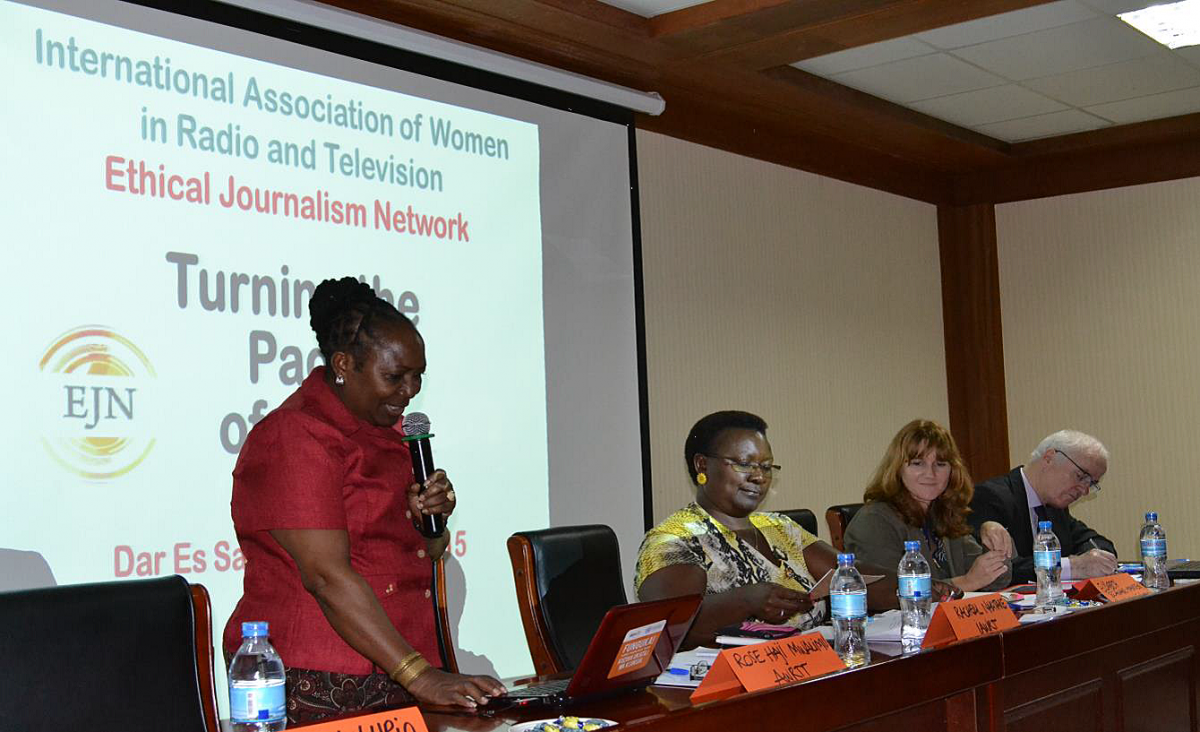

The Ethical Journalism Network campaign for media, ‘Turning the page of Hate’ is being rolled out in Africa in partnership with many organisations, including IAWRT, and will extend to the Middle East and other countries. IAWRT’s Tanzania Chapter and the EJN held one workshop as part of that rollout, entitled: ‘Turning the Page of Hate in Africa; Putting Tolerance on the News Agenda,’ in May 2015. Ckick for EJN presentation. At the Dar es Salaam meeting, some sixty journalists from countries including Tanzania, Malawi, Kenya, Uganda, and Nigeria, spoke about the real consequences of media dissemination of hate speech, such as murder, rape, and genocides in Kenya and Rwanda.

The participants closely examined the media standards which need to be applied to avoid media publicising hate speech or misinformation-information, which fuels division based on gender, ethnicity or religion. On a broader scale, the group also spoke of the need for decent journalist wages to mitigate against corruption and shared information about media restrictions under laws which need to be reformed, or the threats of violence perpetrated by authorities, which can exist even if laws do support media freedom.

Report is available here. Pictured, Left to right: Rose Haji Mwalimu and Racheal Nakitare, IAWRT, Elisabeth Sewabe-Hansen, Norwegian Embassy, Dar es Salaam, Aidan White, Ethical Journalism Network.

The IAWRT Kenya chapter is also working to address gender based technology based violence against women, participating in mapping technological violence against women, with the Kenya ICT Action Network (KICTANet). The project is using the USHAHIDI crowdsourcing tools (ushahidi translates to “testimony” in Swahili, and was developed to map reports of post-election violence in Kenya in 2008). The global map is an initiative of TakeBackTheTech, which allows safe and secure reporting of cases of technology-related violence against women in Kenya, and around the world,The mapping out will contribute towards documenting the occurrence of such violence to bolster the lobbying for increased attention to this growing problem.

Host laws and digilantism

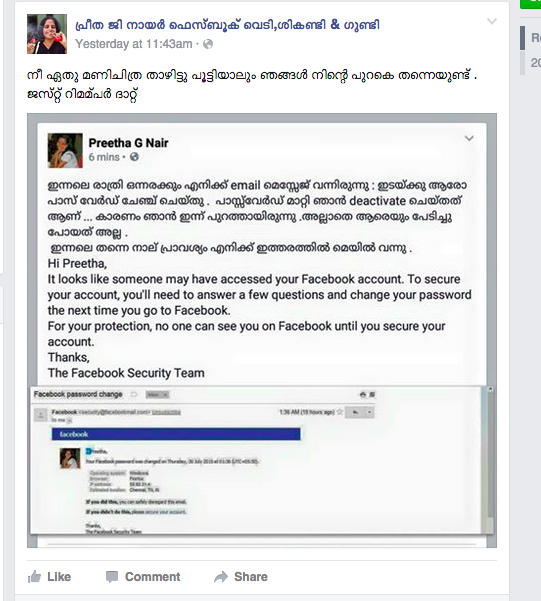

There are so many aspects to the online debate, and Dr Anja Kovacs, the Director of the Internet Democracy Project in Delhi, has pointed to the controvesy surrounding the providers of the online space, such as Facebook. One of its biggest markets is India, with 100 million users, and in the south-west state of Kerala, the story of how Preetha G Nair was removed from Facebook after she and supporters were subjected to a political campaign of sexualised bullying and harassment, is one lesson on how the media multinational is failing to cope with the need to enforce consistent ethical standards across cultures More details here.

One of its biggest markets is India, with 100 million users, and in the south-west state of Kerala, the story of how Preetha G Nair was removed from Facebook after she and supporters were subjected to a political campaign of sexualised bullying and harassment, is one lesson on how the media multinational is failing to cope with the need to enforce consistent ethical standards across cultures More details here.

Facebook had 1.55 billion monthly active users across the globe in the third quarter of 2015, more than half the world’s population. It next closest competitor is the Chinese social media. Facebook continues to expand, even planning to use drones to provide bandwidth in inaccessible areas such as the Philippines and Zambia, according to Mia Garlick, the Director of Policy and Communications for Facebook Australia and New Zealand. She told a conference, at the University of Sydney in Australia, that the organisation promotes “digital citizenship” which is not based on any country’s law, but “a community.”

At the September 2015 forum, GTFO – Empowered Users, Objective Violence and the governance of Social Media, she faced criticism about her organisation’s failure to remove hate speech material at the request of women users. Ms Garlick surprised many there, by saying that Facebook sets a higher bar if the person involved has a “public profile”. In one Australian case, feminist and writer Clementine Ford faced trolling abuse and threats after a provocative attack on a TV program which claimed that women were culpable victims of ‘revenge porn’ because they had taken photos which were later used to shame or threaten them. After reposting the threats and abuse that she received. she was banned from Facebook for ‘violating community standards’. Ms Ford has requested police action against her abusers, and has reported one abuser to her employers, but continues to be abused.

Women who take on sexism and misogyny online, have been particular targets. One of the more disturbing acts of digital violence directed against Canadian American cultural critic Anita Sarkesian reached disturbing heights with an interactive game encouraging users to digitally beat her up (pictured in the EJN presentation at the IAWRT biennial). However, the threat to Sarkesian and gaming developer colleagues, who criticised sexism and misogyny in the gaming industry, was real. It included doxing (revealing personal details such as their address) forcing some to flee their homes. Sarkesian’s ‘crime’ was to set up a website called Feminist Frequency which hosts a video web-series described as “an educational resource to encourage critical media literacy and provide resources for media makers to improve their works of fiction.” Many applaud her stance. The episode is known to many as the ‘gamergate’ controversy. The observation that online discussion of sexism or misogyny quickly results in disproportionate displays of sexism and misogyny, has become known as ‘Anita’s law’ in a list of patterns of behaviour experienced by women online.

Feminist digilantism

Frustration with inaction from platform managers can lead to a more personalised reaction, as well as re-posting abusive or threatening comments, some track down abuseers – a ‘feminist digilante’ response. One such case is that of Alanah Pearce, an Australian gaming journalist, based in the United States, who exposed the perpetrators of sexualised violent threats made against her, to their mothers. Whilst accepting that it may well be a reasonable response, Dr Emma Alice Jane from the University of New South Wales, is critical of the international media embracing it as the perfect solution to rape threats online. “…don’t worry about the police or the platform managers just go to the real source of authority – go to the mothers – take it back into the home, take it back into the private sphere, this is an individual problem, deal with it privately.” Dr Jane says this harks back to a time when feminists argued against the notion that rape and domestic violence and workplace harassment were private issues to be dealt with individually and domestically. Audio Interview here.

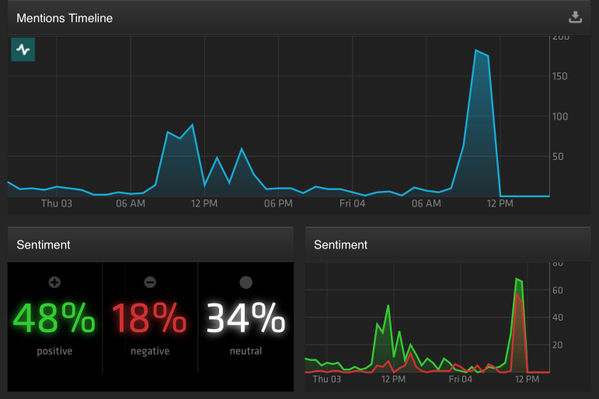

At the forum where I interviewed Dr Jane, the reality of Anita’s law became all too apparent. As the proceedings were live-cast and academics tweeted about the discussion, the reaction online was monitored by the Media and Communications Department, it tweeted “Interesting to see massive jump in conversation & negative terms with speakers on gendered hate”.(see graph,left)

At the forum where I interviewed Dr Jane, the reality of Anita’s law became all too apparent. As the proceedings were live-cast and academics tweeted about the discussion, the reaction online was monitored by the Media and Communications Department, it tweeted “Interesting to see massive jump in conversation & negative terms with speakers on gendered hate”.(see graph,left)

Global solutions?

This years UN report on cyber violence against women and girls says the threat of physical violence is a problem of pandemic proportion when one in three women will have experienced a form of violence in her lifetime: “and gendered cyber violence could significantly increase this staggering number .. as reports suggest that 73% of women have already been exposed to or have experienced some form of online violence.”

The answers are not going to be simple, or perhaps even global. As much as Facebook or Renren.com or Weibo or Twitter or other mass platforms would like to have their own ideal sets of rules, to reduce their liabilities, they must not evade their reponsibility to protect their users from gender based online violence. However, Dr Anja Kovacs says the way forward requires care, given that laws to protect safe online speech can be used to censor. “We need to think through what policies we want … it is important that we do not cede the online space, but we should not ask for laws that come back to haunt us.”

Conference feature Speaking Truth to Power available Here.

Full conference report available here.